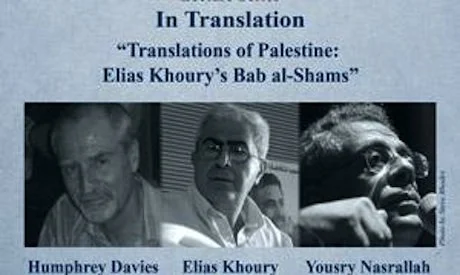

Translations of Palestine: an evening with elias khoury, humphrey davies, and yousry nasrallah

The world holds its breath in anticipation: in a matter of days, the UN verdict on the Palestinian bid for statehood will be revealed, placing some countries on one side of history, the rest on the other yet again. Amidst an atmosphere filled with hope and speculation, one thing is certain: the Palestinian is the person of the hour. Beyond the UN halls, and White House corridors, beyond world delegations and top-secret negotiations, one place cut right across borders and bias, diplomacy and fallacy to get to the heart of the matter.

Last week, The Center for Translation Studies at the American University in Cairo hosted a lecture as part of its In Translation series entitled Translations of Palestine: Elias Khoury’s Bab al Shams. Author Elias Khoury, filmmaker Yousry Nasrallah, and translator Humphrey Davies, three of the leading figures in their respective fields were on hand to discuss the story that has acquired the status of a founding Palestinian alternative narrative. They also discussed their intimate relationship with Palestine across their respective mediums, their distinctive roles as mediators between cultures, and the significance of placing Palestine on a global map through their respective translations.

The evening started with a prologue by Khoury, “Everything we do,” he said “is a translation of the self.” A Palestinian by choice, and a Lebanese by origin, Khoury explained that writing this novel was his way of translating his love for the Palestinian people, for the Palestinian as a human being. He was quick in making the distinction between the Palestinian as a human being and Palestine as a “cause”, an abstract idea. For more than 60 years, Palestinians have endured not just a lack of representation, but a misrepresentation that has systematically aimed at dehumanizing, if not erasing them from existence. History is written by the victors, whereas stories are written by the victims. And so, writing this story was his way of recognizing what history has chosen to overlook. “It was an extremely painful process,” he said, “for it took seven years to write.” Seven years of delving deeper and deeper into the experience of dispossession, to fill up the gaps in memory, to try and save it from its own erosion. And now that the story is written, he feels like he has ceased to be its author and that it wrote itself. For the deeper he delved into the lives of these characters, the more he ceased to exist as a writer, and the more the story took a life of its own.

In describing the process of compiling material for the story, Khoury told of 30 years’ worth of interviews and conversations in the Palestinian refugee camps in Beirut. There, he got to absorb the stories firsthand, without the aid of a pen or a recorder. “It was about capturing the atmosphere,” he said. The aim was to be as true to the story as possible, to achieve a deeper and more intimate form of translation, one that gives more weight to feelings and the essence of the inner self.

In his quest to build a new relationship with reality, Khoury also explored a different narrative technique, one that experiments with structure and syntax. He argued that the nakba did not happen in 1948. The nakba happened and continues to happen with no clear end in sight. For as long as the Israeli occupation is a reality, the nakba is a living and breathing catastrophe. Hence, the story is an unfinished one and cannot lend itself to a conventional narrative structure with a clear beginning, middle and end. The narrative had to reflect a state of existence, and so just like his characters are lost and disoriented, the story too moves in a non-linear way, back and forth across time and space.

But how can you piece together the fragments of a story, muddled in loss, confusion and disorientation? How can you sum up 1001 stories in just one story? Khoury here resorts to the narrative structure of 1001 Nights, weaving together a rich tapestry of stories within stories bound together by the collective experience of pain, with no apparent end in sight. Stories that mirror each other, talk to each other and even use telepathy to communicate with each other. This formed a new kind of dialogue, between stories rather than characters and inner thoughts rather than conversations.

There’s a conflict here: even though it is apparent that the disruption of narrative is there to reflect a disruption in reality, the author insists that the story is not analogous. “There are no metaphors in this story. Yunis is not a metaphor, nor is the hospital or the cave. It is your interpretation (the reader’s) that is a metaphor, in that it inspires you to read the text in a certain light. Hence, the real writer of this book is the reader.”

Yousry Nasrallah, director of Bab al Shams, shared the same opinion about metaphor and interpretation. In fact, writer and director shared the same outlook on many fronts. Nasrallah explained that there’s no room for metaphor in cinema, because as a medium it is visual and deals with the concrete. Things can be interpreted metaphorically, but the director needs to interpret them visually. A place in a movie cannot be “like” something else. When you strive for a poetic representation in cinema, you cannot rely on analogy in language. “A cave is a cave,” he agreed. But if he wants this cave to be a hide-out for lovers, he will need to internalize the experience and imagine what he would do if he were to romance a lover in a secret location. Would he light the place with candles? Would he strew roses on the floor?

For Nasrallah, the story of Bab al Shams is not a metaphor. “To read a great book, is to live a great life.” It is a story that he as a person fell in love with, a story that marked him and corresponded to a need in him. The nakba is a crisis that engulfed the whole Arab world and redefined not just the Palestinian, but ‘the Arab.’ As Arabs, the chain of defeats became the crux of our existence, of our identity. Through a combination of state oppression, manipulation and propaganda, this identity was taken away from us. To deny an ‘Arab’ his identity is to emasculate him and thereby control him. And so systematically, over the course of 60 years, oppressive regimes worked hard to muffle the voices of protest and distance the people from the Palestinian cause.

For Nasrallah, Palestine really ceased to be an abstract idea when he lived in Beirut between 1978 and 1982, at the height of the civil war in Lebanon. It is there that the Palestinian story became one of people rather than a cause, where ‘Yunis’ became a fighter and a lover rather than a hero.

When Nasrallah first read the book in 1998, he was struck by two things, he said. One, that it would make a great movie, and two, that unfortunately no Arab or foreign producer will be willing to finance it. Years later, when the European TV network Arte approached him to make a movie about Palestine, he questioned their motives. Why would they approach an Egyptian director for this project, he wondered. Is it because we made peace with Israel? Did they think that would change the facts? Change the narrative? Luckily enough, the network just wanted him to make “a good movie.” And with that came his insistence that the only movie he wanted to make about Palestine was Bab al Shams. The movie was given the go ahead. And from then on him, Khoury, and screenwriter Muhammad Suwaid embarked on the journey of adapting, or ‘translating’ if you will, the book into a screenplay.

“It was torture!” Khoury exclaimed. As an author, he was already saturated with the story and its characters. They were too real to him and there was no room for interpretation. And so the process of appropriation began for the director, in which he had to make the story his own. To begin with, to realize the epic dimension of the book, the director felt it necessary to divide it into two parts: One dealing with the 1948 exodus, the other, with freedom fighting and life in the refugee camps. For the epic dimension Nasrallah invoked the myth of Palestine based on the tales passed down by our forefathers: Palestine as the land of milk and honey, Palestine as the land of the orange trees and so forth.

Then came the big question of the ending and the surreal phantom scene. In Khoury’s book, the phantom is Yunis’ wife, Nahila, coming to save him from his death and hence, the death of the story. For the director, Nahila reappearing as a phantom after four hours of watching her on screen posed a problem. “It would’ve been tacky,” he said “and unsettling for the viewer.” Here again Nasrallah had to be freed of the shackles of the text, and ask himself new questions about the characters.

It is this plethora of stories and possibilities that attracted Humphrey Davies to the novel as well. “The book is a universe,” he explains, “whose atom is the story.” To engage in one is to engage in all, ad infinitum. For Davies, it was this relativity and ambiguity that renders the absolute need for it to be translated. We begin the story at the end, which arguably can also be seen as the beginning. “With each story throwing the gauntlet at the feet of another story,” art imitates life and that is the ultimate challenge and reward. To write the story, the Queen of Hearts tells Alice, “You begin at the beginning and go on till you come to the end: then stop.” But this is no ordinary story. This is the story of Palestinian history, its people, neighbors, fighters, mothers and lovers. It is a story that carries us right to the heart of the experience of dispossession and hence, cannot start with ‘once upon a time.’ The only fitting beginning is that of the main character, “Would you like to know what happened to me?”

The evening ended with a collective feeling of elation and an uproar of applause. Whether the same fate awaits Palestinians in the UN this week is yet to be seen. One thing that reassures me now is that Bab El Shams does not end with a full stop, neither will the fight for Palestine. In the words of our poet Mahmoud Darwish -so beautifully invoked in Mahmoud Abbas’ UN speech, “Standing here, staying here, permanent here, eternal here, and we have one goal, one, one: to be.